by Shanti Elliott and Carol Redfield-Mims, with Suzanne Amra, Maryam Bilal, Jereece M. Brown, Gael Byrnes, Martria Clifton, Kassandra Cosby, Olivia Cote, Shauna Davis, Roshunda Harris-Allen, Nicol Hemphill, Jacqueline McClendon-Griffin, and David Stieber

“People in Mississippi are good at doing things that have never been done.”

- Jackson Historian Mr. Franklin Figgers

“To know where you are as an individual and as part of a collective group, you have to know from where you came.”

- Chicago teacher Ms. Jereece Brown

In the fall of 2017, 14 teachers from Jackson, Mississippi and Chicago, Illinois began meeting to share stories of their cities and classrooms. They were preparing to participate in an annual meeting of educators focused on equity in education, called the North Dakota Study Group because it began in 1972 in North Dakota. This year the Study Group meeting would be held in Jackson, hub of ongoing collective work for liberation and democracy, where the fight for fully funded, vibrant schools is understood to be a continuation of the Civil Rights work led by Fannie Lou Hamer, Medgar Evers, Bob Moses and other Mississippi leaders.

The North Dakota Study Group (NDSG) invites you to Jackson, Mississippi, a singular place in the African American struggle for emancipation. Rich historic sites in Jackson celebrate the courage, creativity and perseverance of activists who were part of Freedom Summer and the Civil Rights Movement. Jackson leaders of today are no less challenged by policies that condone violence, white supremacy, police brutality, and lack of access to healthcare, housing, jobs, and more. Of particular concern for NDSG will be access to the emancipation that can occur through education, including our own emancipation from racism. https://ndsg2018.weebly.com/

The teachers of Jackson and Chicago, two cities joined by a common legacy of Black resistance to systemic racism, sought to build conversation and relationship between their students in the months leading up to the Jackson NDSG meeting. A Jackson teacher described her goal in participating, “to partner with schools doing the work of transforming our schools as a place for cooperative learning and students to benefit from these new opportunities.” A Chicago teacher noted,

The first thing that comes to mind is my students’ family connections to Mississippi, and the history of migration from Mississippi to Chicago. We could learn about each others’ family histories, migration and non-migration – comparing and contrasting life and social justice issues between the two communities. A project could take form through many angles – by reading literature/art of each community, by researching family histories and migration trends, analyzing the impact of individual choices and the impact of the environment, etc. I am in charge of initiating our first year-end “capstone” project, and I see a collaboration as a unique learning experience that that provides leadership and collaborative possibilities for students in both locations

(Teacher application, Jackson-Chicago Teachers’ Exchange, Fall 2017).

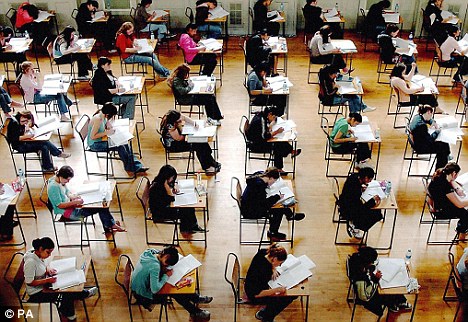

In Jackson and in Chicago, public schools are under-funded, over-tested, and racked by the broader economic and social issues of their cities. The schools are also full of curious students, visionary teachers, and committed family members who teach and learn in powerful ways that are disregarded by the deficit narrative about public education, and especially public education in Jackson and Chicago. They share a vibrant history and current reality of communities who organize social change around love for and protection of young people. So, while teachers were interested in building relationships between their classrooms, they also shared a vision for dignity in schools, authentic community-based learning, and social justice.

For the first several months, meetings were held online and by telephone, so that participants could learn about each other’s interests and teaching approaches, and share challenges each teacher experienced in their own contexts. The teachers taught diverse subjects and grade levels, but quickly found that they shared a commitment to restorative practices as a support for improving relationships between students and between students and teachers.

Over the course of the year, the Jackson teachers traveled around the country deepening their understanding of restorative justice. They brought back to JPS new methods and perspectives and led peace circle training for students, teachers, and parents in the district. Meanwhile, Chicago teachers practiced restorative justice in their contexts, with the support of professional learning offered by youth leaders of VOYCE (Voices of Youth in Chicago Education). The teachers from the two cities talked periodically, sharing new learning, questions, and applications in their schools. In one public example of the teachers’ exchange, Jackson teacher Dr. Roshunda Allen and Chicago teacher Mr. David Stieber connected in a Facebook Live chat to discuss educational issues impacting educators in Jackson and in Chicago. For instance, they reflected on the racial disparities underlying current public attention to gun violence in schools: “gun violence has been impacting communities of color for years but it is only now after a shooting at a white school that everyone seems to care.” The educators’ dialogue emboldened them to develop an analysis of the impact of systemic injustice on their students and bring it to a more public stage, to promote education that values the lives and believes in the dreams of all students.

To prepare for the Study Group meeting, teachers steeped themselves in Civil Rights history as well as current realities. With the rest of NDSG, they read I’ve Got the Light of Freedom, Jackson Rising, A Different Kind of Takeover for JPS, and other Readings. They came to the February 15-18, 2018 Study Group meeting in Jackson primed, as NDSG’s invitation urged, to think about personal experiences in relation to a legacy of white supremacy in this country and to engage in conversations about education based in equity and justice. NDSG Jackson Host and Institute for Democratic Education in America Director Albert Sykes challenged participants to ask, “How do we put ourselves in the story? It’s not about coming to Jackson,” he said, “it’s about sinking in to Jackson. Not a drive-by, but a serious focus on race, on equity. If we can see what’s happening, we can know where we are.”

In February 2018, educators from all over the country came to Jackson with questions about national education policy and practice paired with intentional inquiry into the city’s local context: How can we learn to be in this place fully and respectfully? How does my being here help me learn more about myself and my world? How does it impact my students when I follow Ella Baker’s lead, and sit at the feet of people who stood up when pushed down? What does a grassroots approach to change look like in education and in politics?

Participants of the meeting visited the Civil Rights Museum and the NAACP, mourned Medgar Evers and the thousands of victims of white supremacist violence, and at the venerable

HBCU Tougaloo College, sat together in conversation about approaches to education that combat racism and grow what keynote speaker Ms. Rukia Lumumba called “collective genius.” She sparked questions for educators: Why hasn’t it been part of my education, to vision and dream? Who is served by my obedience to the accountability systems that are in place in my area? Why do I perpetuate approaches to education that don’t ground students and teachers in their capacities to collectively, boldly, creatively vision?

The Study Group focused on challenges to equity in education, in a context where the state has condemned Jackson students to what Mr. Albert Sykes names, “a sharecropper’s education.” Local leaders situated the vulnerabilities of the school system. They noted that the threatened state takeover of the schools stemmed from the fact that “Jackson never healed the gaping wound of slavery and Jim Crow.” They also emphasized the resilience and resourcefulness of the people of Mississippi, whose work led to the Voting Rights Act and other critical social advances. In the 1960s, local leaders like Fannie Lou Hamer took on the national Democratic Party though they couldn’t vote themselves. Dignity and collective power was embedded in the buildings like the building NDSG met in, home to CORE, NAACP, SNCC, and many local Civil Rights organizations. We were in, they made it clear, sacred space.

At Tougaloo, the Jackson and Chicago teachers held a fishbowl conversation, surrounded by NDSG colleagues from all over the country. Chicago teacher Ms. Martria Clifton talked about the importance of students sharing stories, being able to say: “Here’s who I am, where I’m from. Here’s what’s going on in our schools.” Jackson teacher Ms. Olivia Cote responded, “we need to create the space for students to explore their identity and be proud of their identity. To share with students who look like them in another area is a way to build their identities up.” The teachers shared approaches to community-based civic engagement: Teachers and students researching their communities, oral histories, studying statistics through histories of local housing, and restorative practices in the classroom and community.

NDSG colleagues sat in a circle around the teachers. They listened closely, then offered observations and support:

“This is a critical platform for building dialogue.”

“How are you building trust amongst yourselves? When educators take the time to do this, it models relationship-building for your students.”

“A seed has been planted. Protect it. People try to trample on seeds before they have a chance to grow.”

“Unlike the vertical power structures that organize many of our institutions, this is horizontal development – teachers unfolding the lives and the wisdom of teachers.”

“Create the conditions of a no-whine zone. That’s what we’re not doing. Hold up the work of a child with each other.”

In her reflection on the Jackson-Chicago Teachers’ Exchange, Chicago teacher Ms. Shauna Davis wrote, “By exposing and encouraging students to have conversations with a different population than they are used to, we are helping them learn and grow into productive global citizens. We are empowering them to take chances and get to know people, no matter how big or small the difference is.” She emphasizes that supporting students’ development as global citizens requires that educators engage in a particular kind of preparation, one that is deeply reflective and influenced by community-based processes:

I am developing my practice as a culturally sustaining educator. I am learning how to actively communicate with adults and students about race and injustices that are happening in the world. Living in a large city, we are constantly observing injustices on people of color. Students and adults need opportunities to discuss what is happening to us and our students. I am learning through NDSG how to hold and lead these conversations, as well as sharing this information with colleagues so that they can have these conversations with their students too. Through NDSG I am gaining confidence in my abilities and a supportive community (networking) to become a leader in my school community.

We look forward to continuing the Teachers’ Exchange, where educators share their learning with one another and with their students, and invite students into the process of learning about the history, issues, challenges, and connections with the other city.

* The Jackson-Chicago Teacher Exchange is supported by the Mississippi Association of Educators and Chicago Public School’s Department of Social Science and Civic Engagement.